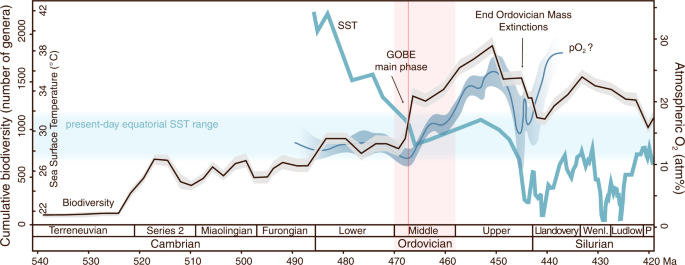

The greatest rise in marine biodiversity in all of Earth’s history surprisingly was not fuelled by ocean oxygenation. Instead, oceanic redox stability appears to have favoured increased ecosystem resilience and – ultimately – a massive rise in global biodiversity levels. Oxygen rise occurred later…

PhD student Alvaro del Rey measured the uranium isotope composition of Middle Ordovician carbonates in Kinnekulle, Sweden, and discovered that the radiation of animals coincided with stable, albeit still more deoxygenated ocean redox conditions than today. Marine oxygen levels increased after the main peak of the biodiversification episode, the study showed.

The new study is published in Nature Communications Earth & Environment.

The official press release from University of Copenhagen is found here.